∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

The Portrait Gallery.

Blest be the art that can immortalize!

The art that baffles Time's tyrannic claim

To quench it.

Cowper.

EDGAR A. POE.

——

BY THOMAS S. COLLIER.

——

In the multitude of his biographies it would seem that one could find all that is interesting concerning Edgar Allan Poe and his life. Yet such is not the case. Poe was known to many people, and left reminiscences of his peculiar manner and thought wherever he sojourned. He was one of those who possess two characters; each essentially different from the other; each supreme in control while it held the ascendency, but neither strong enough to hold continuous rule. When his intellectual powers reigned, Poe was a brilliant, kind-hearted, honorable man, and more industrious than are most men. This was his true self: the one by which he should be judged. When his sensual passions obtained the advantage, he was like one subject to periods of inherited insanity. The fault was not his, for he fought desperately against it, but was the result of a weakness he was not accountable for. It was this strange combination in his nature that made him a man to be remembered, and his appearance, actions and conversation impressed all he met with recollections beyond the reach of forgetfulness.

Edgar Allan Poe was born at Baltimore, in January 1811. His parents died while he was a mere child, and Poe was adopted by Mr. John Allan, a wealthy merchant of Richmond. His genius soon made itself known, and the erratic nature also developed rapidly. His education was partly acquired in England and partly at the leading institutions of Virginia. His conduct during a period of mental aberration caused him to be expelled from college, and he set out to join the Greek patriots. He never reached Greece; but wandered to St. Petersburg, from whence he returned to the United States, and received [column 2:] an appointment at West Point, to lose it within a year. In 1829 he published, at Baltimore, a small volume of poems, entitled, “Al Aarooff [[Aaraaf]], Tamerlane, and Minor Poems,” and shortly afterward married his cousin, the beautiful Virginia Clemm. From this time out he devoted his attention to literature, producing some of the most musical poems, weird stories, and bitter criticisms, in our literature. The circumstances of his death are too well known to need repeating. It took place on the 7th of October, 1849, when Poe was thirty-eight years old. Had his mind been better balanced, and his genius been the same, would undoubtedly have left a fame that no other American could equal.

His poetic genius was eminently lyrical, and there is a music in his work that has been reached by but few. It has lately become the fashion to disparage his poetry, but no critic can destroy its charm. That it has a somber cast is undisputed, but it also possesses a melody that sweeps one along through an enchanted realm of “dim vales and shadowy woods, and, music-haunted floods,” and leaves a memory that grows stronger instead of fading into a dim vagueness.

Poe's poetry was of a subtle order, depending much on art and sound, but with a mystic undercurrent of beautiful and dreamy thought — thought not always of a healthy tone, yet rich in a nobleness that acted strongly on kindred spirits. It has been said that he used the poetic form to express sound simply, but this I deny. In “The Raven,” which is a finished work, there are pictures that cannot be put away

“The silken, sad, uncertain

Rustling of each purple curtain”

seems to speak of a shadow-filled casement, opening on dreary distances of night, with a ghostly breeze moving them to and fro. In “The Haunted Palace,” “Eldorado,” and a score of others, the same subtle power is shown — a power that conveys by implying, and which builds foundations from whence spring airy and undying pictures. If Poe's poetry was not of a powerful order it could not do this. Sound alone cannot produce a lasting [page 362:] impression. It is the spirit of the music that makes it remembered; it is the strength of the poem that stamps it undying.

But this article is not intended to give a critical estimate of Poe's poetry. It was begun with the idea of embodying some scraps of poetry and reminiscence, and thus adding a mite to the store of resources at the future biographer's command.

Poe's manner of composition, and the stimulus that gave his poems vitality, have often been subjects of discussion. He gave us a very careful essay on the “Philosophy of Composition,” taking his poem of “The Raven” as an example. While not questioning the truthfulness of its statements with regard to “The Raven's” birth, I think that generally his poetry came spontaneously, and was afterward subjected to careful study and polishing.

His weird and strangely sweet poem of “Ulalume,” a poem that very few of his critics comment on — a silence that is very strange, as the poem is one of his most finished and powerful productions — was the spontaneous result of an act liable to occur only in the life of a man of Poe's temperament. The pathetic little history is thus told in a letter written by one of his dearest friends to whom he narrated it:

“On the anniversary of Mrs. Poe's death — which, however, was not in October, but January — her husband walked till morning through an avenue of trees, leading, I think, from the bridge built over the Harlem aqueduct; not far distant was the tomb in which her remains rested. Toward morning the profound melancholy which had oppressed him yielded to an unwonted serenity as he looked up and saw the morning star — Venus, Astarte, the star of love — rising in the east. He felt new-born hopes kindling within him, and believed that his life would not be forever desolate; but at this moment he observed that beneath the star lay, cold and chill, the tomb of Virginia, and the hope inspired by this ‘sinfully scintillant planet” [[’]] died away into more profound despair.

“These were the facts from which this poem of strange enchantment was unfolded.”

As the poem originally stood it had an additional stanza, which he omitted at the suggestion of the friend whose letter has been quoted, as this omission gave the piece a more complete ending. The discarded verse is, as this friend says, “fine and fearfully suggestive,” and we quote it, never having seen it in print

“Said we then — the two then — ah, can it

Have been that the woodlandish ghouls —

The pitiful, the merciful ghouls —

To bar up our pathway and ban it

From the secret that lies in these wolds —

From the thing that lies hid in these wolds —

Have raised up this spectre of a planet

From the limbo of lunary souls!

This sinfully scintillant planet

From the limbo of lunary souls,

From the hell of the planetary souls?”

While speaking of poetry it will be proper to give a poem which the London Mirror lately published, saying that it had no doubt concerning its being Poe's work. So many spurious pieces have been published, purporting to be Poe's, that there is naturally a hesitancy about advancing any endorsement of poems not having the stamp [column 2:] of his signature. The editor of the Mirror makes this explanation:

“When Poe, in 1845, acquired sole possession of the Broadway Journal, he began republishing his poems in it, but without any signature. Most of these pieces have been included in the collections of his poetical works, but the following, ‘To Isadore,’ appears to have been overlooked by all his many editors, who, indeed, have for the most part contented themselves with what came to hand, without going to the trouble of poring over dusty files of old newspapers, that had to be searched for. The piece comes to us through the courtesy of a valued contributor, who has made the life and works of America's most original poets a life study. We think the poem thoroughly in Poe's style. The third stanza is a perfect gem, equal to anything in the collected works, and the ending of the third and fifth stanzas is thoroughly characteristic of the poet's earlier style.”

So much for the editor of the Mirror. Here is the poem:

TO ISADORE.

Beneath the vine-clad eaves,

Whose shadows fall before

Thy lowly cottage door —

Under the lilac's tremulous leaves —

Within thy snowy, claspèd hand

The purple flowers it bore —

Last eve, in dreams, I saw thee stand

Like queenly nymph from fairyland,

Enchantress of the flowery wand,

Most beauteous Isadore!

And when I bade the dream

Upon thy spirit flee,

Thy violet eyes to me

Upturned, did overflowing seem

With the deep, untold delight

Of Love's serenity;

Thy classic brow, like lilies white,

And pale as the imperial Night

Upon her throne with stars bedight,

Enthralled my soul to thee!

Ah! ever I behold

Thy dreamy, passionate eyes,

Blue as the languid skies

Hung with the sunset's fringe of gold;

How strangely clear thine image grows!

And olden memories

Are startled from their long repose,

Like shadows on the silent snows

When suddenly the night-wind blows

Where quiet moonlight lies.

Like music heard in dreams,

Like strains of harps unknown,

Of birds forever flown —

Audible as the voice of streams

That murmur in some leafy dell,

I hear thy gentlest tone;

And Silence cometh with her spell,

Like that which on my tongue doth dwell

When tremulous in dreams I tell

My love to thee alone.

In every valley heard,

Floating from tree to tree,

Less beautiful to me

The music of the radiant bird,

Than artless accents such as thine,

Whose echoes never flees!

Ah, how for thy sweet voice I pine!

For uttered in thy tones benign

(Enchantress!) this rude name of mine

Doth seem a melody!

In comparing this poem, to see how it agrees with Poe's other work, we find that there is the same flow of [page 363:] rhythmic cadence in it that individualized all the verse he composed; a sweep of sound that made the idea more a vehicle to express its beauty, than a ruling power. There is also a use of words that were peculiarly Poe's. Not that this is any rule to set faith in, but when they occur in conjunction with a manner of thought and style so similar, they are apt to carry weight. Another characteristic that reminds one of Poe is the upward sweep of the poem, rising through each verse to better things. The third stanza is, as the editor of the Mirror says, a fine one, and startlingly like Poe's early work, in which the influence of Tennyson is plainly visible, especially the influence of the first two volumes of Tennyson. Poe was impressible, and he caught the tone and color of any style or thought that pleased him and insensibly merged it into his own work. We are led, therefore, not on the strength of our own judgment alone, but after consultation with several people who know Poe's style and manner of thought well, to ascribe this poem to him.

Before beginning this article we were so fortunate as to secure the assistance of Mr. William H. Starr. Mr. Starr was, at the beginning of Poe's connection with the Broadway Journal, publisher of that paper, and was thus enabled to see much of him. His recollections possess the charm of freshness, as they have never before been given to the public. In them will be found a corroboration of our estimate of Poe's character — an estimate that was formed before we had the pleasure of meeting with Mr. Starr. We will let Mr. Starr give his impressions of Poe in his own way, as this adds to their strength:

“My first acquaintance with Edgar A. Poe was after his removal to New York from Philadelphia. This was in the early part of 1845. He had been engaged by Gen. Morris and N. P. Willis on the Mirror, but soon afterward became associated with Mr. Briggs on the Broadway Journal, with which his connection continued until its publication ceased, in January, 1846. During the last six months of its continuance he assumed the entire charge and responsibility of the paper. His pecuniary embarrassments increased to a degree so harrassing [[harassing]] as to discourage any person of ordinary energy. His was a nature, however, to persevere in his favorite undertaking, and he labored with almost superhuman effort to overcome the disadvantageous circumstances by which he was surrounded. His efforts, however, were unsuccessful, and under the depressing influence of his position it is not strange that he failed. With an invalid wife, whom he almost idolized, at his scantily furnished home, and want and privation her as well as his heritage, it is not singular that his efforts should have been fitful and irregular, and his brilliant intellect shadowed at times by despondency and morbid influences.

“Naturally modest and deferential in his manners, he combined a graceful demeanor and cultivated taste with impulsive ebullitions and morbid fancies. Mr. Poe was a person who deserved that sympathy from his friends and the public which his occasional outbursts of feeling and unguarded expressions too often repelled. He was amiable, and not ungrateful for favors. In the privations that he endured during the latter years of his life he suffered keenly — more deeply than the public, or even his intimate literary friends, were aware; ‘Gratefully, most gratefully yours,’ was appended to more than one note acknowledging favors received. This really was the exhibition of his true nature, when not unbalanced by his insidious foe. The morbid mistrust he sometimes exhibited [column 2:] in his intercourse with men was not extended toward women.

“I do not think, with Mr. Griswold, that ‘he had lost all faith in man or woman;’ on the contrary, the latter was his ideal of perfection, beauty and loveliness. His ‘Annabel Lee,’ and other poems, all attest this. His own amiable wife and devoted mother-in-law he almost worshiped, and his regard for woman was a noted trait in his erratic character. It was at his own home and in the presence of his family that his true nature was fully exhibited. There his playful and affectionate disposition was manifest, and his social and child-like nature exhibited in its true colors a very different light from that in which he was generally regarded, by even his own intimate friends and literary admirers.

“Mr. Poe's imagination was quick and fertile; his genius peculiar and unique. The brilliancy of his mind and the exuberance of his fancy could scarcely be equaled, but his imagination seemed naturally to seek and dwell on the dark and melancholy in the natural and supernatural. His conversational powers were rarely excelled. Often have I seen him, while he was editing the Broadway Journal, seated at the little side desk he used in the office in Nassau street, with a circle of literary friends gathered around his chair, completely entranced by his eloquence; his impassioned utterances and magnetic fascination, his words, and often full sentences, sparkling and glowing with a more than diamond radiance: and this even when his mind was shadowed by trouble and despair.

“Mr. Poe was never an idler. When engaged on any paper as editor, his attention to his duties was noted, and he did what he had engaged to do well.

“With feelings of sadness I recur to Mr. Poe's misfortunes, and his weakness under his pecuniary embarrassments. He brooded over the somber picture until it became a sort of second nature to do so. Often reduced to extreme poverty and want, his wife a confirmed invalid, and his home destitute of the comforts and even the absolute necessaries of life, he would sometimes walk the deserted streets alone and at midnight, frequently amid storm and tempest, drenched to the skin and shivering with cold, lamenting his unhappy fate and invoking aid from the ideal spirits his own fancy had created, scarcely conscious of himself or his condition, and giving no heed to the objects by which he was surrounded.

“It is not singular that in his occasional morbid intervals he was betrayed into irregularities that essentially marred his usefulness as a writer or a critic. In his unguarded moments he would resort to the wine-cup as a remedy. From the weakness of his physical constitution he was peculiarly liable to be overcome by its influence. A single glass would arouse his dormant feelings and change his whole nature. His will seemed peculiarly affected, and under this influence was specially excited. The unsparing severity of his sharp criticisms, and the apparent incoherency of some of his productions, may be attributable to this cause. In fact, at these times he was controlled by a temporary insanity — the ban of a brilliant, but not evenly balanced, mind.”

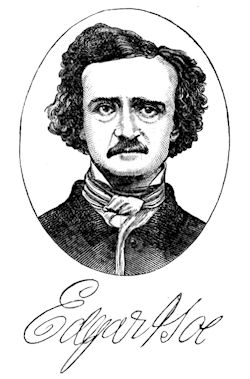

This is Mr. Starr's account of Edgar A. Poe — an account that differs in many points from that given by other of his contemporaries. Being the impression that has lasted through many years, it is but reasonable to consider it the one based most strongly on a true foundation, and we feel sure that it will be gladly read by many admirers of Poe. Our portrait was made from a newly discovered likeness, taken in Providence, during one of Poe's visits to a well-known literary lady of that city. No copy of it has ever before been published.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

Notes:

Like so many biographical articles of the era, the present essay is full of errors and misconceptions derrived mostly from other biographical articles. Poe was not born in Baltimore in 1811, but in Boston in 1809. This error was repeated in many biographies of Poe published before 1875. The portrait is an engraving of the “Ultima Thule” daguerreotype.

“To Isadore” was actually by A. M. Ide, Jr. The poem was printed in the London Mirror by John H. Ingram, who erroneously presumed that “A. M. Ide, Jr.” was a pseudonym for Poe.

The image is a woodcut engraving based on the “Ultima Thule” daguerreotype of Poe that belonged to Sarah H. Whitman, of Providence, RI. The same image also appears on the cover of the issue.

There was a William H. Starr who was listed as editor and proprietor of the Farmer and Mechanic (New York, NY), beginning about April 1845 and until at least the end of 1849. Beginning with the issue for March 8, 1845, the publisher of the Broadway Journal is noted as John Bisco. Earlier issues do not list the name of a publisher, but the prospectus fot the Broadway Journal of January 4, 1845 mentions Bisco as the publisher. Bisco continued to be the publisher until Octover 24, 1845, when Poe bought out Bisco's interest in the paper. Thereafter, Poe is noted as the editor and proprietor, but beginning with the November 1, 1845 issue, there is a note at the end stating that the journal was “printed at the office of the Farmer and Mechanic.” Therefore, while the claim that Mr. Starr was the publisher of the journal may be something of an exaggeration, he does appear to have had some connection as the printer.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

[S:0 - CH, 1878] - Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - A Poe Bookshelf - Edgar A. Poe (T. S. Collier, 1878)