∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

[title page:]

M

ABBOTT

AS POE SCHOLAR

The Early Years

MAUREEN COBB MABBOTT

Acknowledgments

Jay B. Hubbell, late Professor Emeritus of English at Duke University, said, “Thomas Ollive Mabbott is the Poe scholar of his generation and this story of his early years makes him come alive for me.”

Dr. Hubbell requested the writing of this essay for the Jay B. Hubbell Center for American Literary Historiography at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. Upon learning of its pending publication, he planned to write an introduction — a task he left unfinished at the time of his death in February 1979.

The Enoch Pratt Free Library, the Poe Society of Baltimore, and the Library of the University of Baltimore are grateful to the Jay B. Hubbell Center and to Maureen Cobb Mabbott for granting them the privilege and pleasure of publishing the essay and thereby sharing it with Poe enthusiasts and admirers of Professor Mabbott’s work throughout the literary world.

1898-1968

Contents

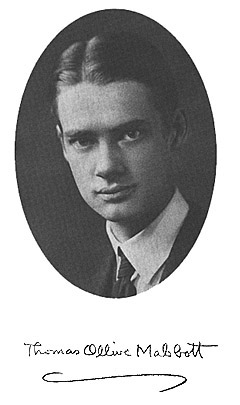

| Frontispiece: Thomas Ollive Mabbott in 1923 | ||

| Introduction | 1 | |

| I | Early Youth | 2 |

| II | Collecting | 3 |

| III | Emphasis on Poe | 5 |

| IV | Specialization — Politian | 7 |

| V | Diary of Poe Activities | 10 |

| VI | The Summing Up | 19 |

| Epilogue: Favorite Poe Poem | 23 | |

| Appendix: Seeing Poe’s Tales and Sketches through the Press | 25 | |

| Informal List of Books Published by T. O. Mabbott | 33 | |

Introduction

After forty-five years of close association with Thomas Ollive Mabbott, I wish to begin this account with some general statements. He shared, apparently from his earliest years, that passion of true scholars that came into the Western world with the Greeks — the desire to know. What was important to him was to discover, record, and preserve the truth. In the process of doing that he became first a collector and then a student, but he never collected for investment nor studied for improvement. With the exception of sports, business, and possibly some other areas, he was enthusiastically interested in everything, not only in historical facts and accurate texts but in how to tune a piano, to make a souffle, to quiet a baby. He was devoted to facts and believed in them, but in the way that Walt Whitman meant when he said, “The facts are useful and real . . . they are not my dwelling . . . I enter by them to the area of the dwelling.”

I met TOM in the summer of 1923 when, not quite twenty-five, a new Doctor of Philosophy with the edition of Poe’s Politian as his thesis, he had been summoned by John Matthews Manly to conduct a seminar on Poe and Whitman at the University of Chicago. As I was an undergraduate I did not attend the seminar but Rae Blanchard, afterwards professor at Goucher College, told me that when TOM appeared before the group he looked young, awkward, green, and there were titters in the room. He began by quoting Greek, and subjected members of the seminar to a lecture so interesting and so learned that they applauded at the end. I am sure that what he quoted was Greek poetry and what he told them was that although they were to study the works of two great poets, they would not know what great poetry was until they had read the Greek lyric poets in the original language. I was to hear this many times later, as I was to hear much Greek and English poetry quoted, for lyric poetry was his chief love.

Although from the time he was twenty-five TOM’s public image was that of a Poe scholar, the members of his household and, I am sure, the members of his classes knew that the study of Poe’s works was only one of his consuming interests.

I do not know how to avoid the danger that concentrating on his work on Poe involves. That concentration is bound to give a distorted picture of the life of the man whose life story I do not intend to write. Poe [page 2:] was not his whole interest. Shocking as it may seem to some of his fellow scholars, his work on Poe was probably what he once called it, a hobby. How [[to]] reconcile that statement with the reams of meticulous notes and the never-ending search to find the true image of an author quite clever at concealing that image? It is true that, among his other interests, concern for the answers to the many questions about Poe was always there like a tinder waiting for a spark. “That’s where Poe got that!” he would exclaim in the midst of what seemed like casual summer reading. Nothing was casual; nothing, that is, that he let his mind rest on. Quite recently, when I read Henry James’ admonition to a young writer: “Try to be one on whom nothing is lost,” I thought immediately of TOM. Within the area of his attention everything contributed to everything else. And yet even here I may give the wrong impression. TOM was not a hyper-sensitive, pressure-driven dynamo. He was restful, actually, and knew how to play. To some onlookers he presented during his student years a picture of a lean, young scholar awkwardly but rapidly going from one library to another, to auction houses, booksellers, and autograph dealers, while corresponding with learned old gentlemen and coin dealers here and abroad. Others saw another picture. He loved parties and the theatre, knew all the latest songs, went to every musical comedy. When money got low, he and Mott Brennan would dress up in white tie and tails and walk nonchalantly in with the intermission crowd, especially to those shows which once seen had revealed some girl in the chorus worth watching.

I

Early Youth

To begin at the beginning, TOM had very early indeed been fascinated by the ancients. At some quite youthful age, I was told, he fashioned himself a diadem of safety-pins, placed it on his head, and raising a magisterial right hand declaimed, “I am King Hieronymous the Second of Syracuse.” No doubt he had been shown some illustrated dictionary, probably the same from which he learned the Greek inscriptional letters by the time he was nine. This episode seems to have come before he began to cut out and save the gilt pictures of medals on the H-O oatmeal boxes. In all I would suppose that an ancient coin with the [page 3:] portrait of an emperor was the object of his heart’s desire as soon as he learned there was such a thing.

The only child in a Victorian household that included two maiden aunts and often a pair of grandparents, he was much confined, cautioned and protected, dressed up, and in general kept physically uncomfortable. (There is a picture of him as a six-year-old in a white Norfolk suit with his hair artificially curled to fall gracefully around his face.) In that milieu his adventures had necessarily to be those of the mind. There was no rejection, however. Although its territory was severely circumscribed, he was permitted a dog, appropriately named Athena; his juvenile coin catalogues show some initial instruction from his physician father; his great-aunt Jane earned his eternal gratitude by her cheerful chaperonage on trips (weekly, one hour each) to the Museum of Natural History and to the Metropolitan Museum, where the small Tanagra figures of the third century B. C. especially fascinated him. His mother, whose passion was shopping, could be persuaded to include a coin shop in her almost daily excursions to Wanamaker’s. Only his grandfather Ollive, he said, had ever read one of his college books. This meant so much to him that he liked to use the Ollive part of his name. (Thomas Stone Ollive was a self-educated Englishman who, after living an adventurous life in California as a baker in the Gold Rush — where he distinguished himself by never carrying a gun — was, at the time TOM was much in his household, vice-president of the National Biscuit Company.) Although there was no particular mental stimulation, no directing, there was, what was better perhaps, a kindly indulgence in the mental activities of this unusually self-directed child.

TOM started school late and never liked it very much, but Collegiate, the oldest boys’ school in New York, was right for him. There he began the study of Latin in the Lower School, and Greek at the age of fifteen. Probably from the beginning, school interfered very little with his independent studies.

II

Collecting

TOM’s first article, “Some Unpublished Seventeenth Century Tokens,” appeared in the Numismatist when he was fifteen years old. [page 4:] He had begun to collect coins before he was nine with a passionate interest that never ceased as long as he lived. And, as it was by way of collecting that his interest in Poe was ignited, it is necessary to begin an account of his work on Poe with the story of his collections. It was his great good fortune that the very first coin shop he persuaded his mother to enter was that of David Proskey, whose name was known and honored in the numismatic world. It was Mr. Proskey who taught the young collector not to believe everything he saw in print, who introduced him to the British Museum Catalogues, and who said, “Thomas will be a great numismatist some day.” Thus it was by way of its coin department that he was introduced to that great institution, the British Museum, of which he afterwards said that it was one of the two things in the world whose reality had not disappointed his expectations. Long before he made his first meticulous lists of Poe texts, he was listing Greek and Roman coins after the pattern of the British Museum Catalogues. When he was fourteen he met Howland Wood, curator at the American Numismatic Society.

When he was a little older he discovered, as he began to read the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, that the library of his grandfather’s old-fashioned townhouse had on its shelves copies of Godey’s and other magazines containing Poe texts. It occurred to him that such magazines might be valuable, but when booksellers offered twenty-five and fifty cents apiece for them, he felt it was a buyer’s market and began to purchase magazines with Poe texts in them. By the time he was in the Upper School at Collegiate he had become attracted to old newspapers. He searched throughout the United States, mostly by correspondence, for items printed on rag paper before 1890. He began to visit autograph dealers and booksellers, and found he could pick up, for fifty cents or a dollar, letters and books of minor American authors. When he was eighteen his mother gave him one hundred shares of National Biscuit Preferred Stock, saying, “Now Tom can have his own collecting money.” It was a modest yearly sum, but for fifty years it never went for anything else.

All of TOM’s collections were working collections. His coins increased in value not only because of inflation but also because of the Mabbott notes on the envelopes. From the first he had a desire for rarities and would buy a coin just because he did not know what it was. As his knowledge grew, so did the rarity of his coins. He had a feeling for authenticity, a talent more intuitive than learned, which, as he said, was [page 5:] developed by being constantly with the subject. His later, small collection of fifteenth-century prints, the basis of his two seminal articles on these artifacts of the beginnings of printing, became a more distinguished collection, I was told, because it had been studied and catalogued by him. His collection of newspapers, now at the American Antiquarian Society, was thoroughly read and researched by him before it had to be given away in 1930 to make room for a nursery. The Poe magazines he retained in his personal library and read and remembered much of their contents long before he knew he was preparing the true background for his future work on Poe.

The print and coin collections had their own destinies and, although they were a part of his life as a scholar, do not contribute directly to the Poe story, but in his newspaper and magazine collections TOM had beside him, before he was nineteen, an increasing number of the printed texts of Poe’s works, and much of the ambience of Poe’s time. Some of his notes on that author began to appear in the New York newspapers while he was in college, and about the time he graduated from Columbia his “A Few Notes on Poe” appeared in Modern Language Notes. Soon after, he began to make the London Notes and Queries his “outlet.” Neither then nor later was he interested in working up long theoretical articles. I do not think he ever had anything in PMLA. Although he had intuitive gifts that contributed to his research, at heart he was a scientist and was interested in discovering facts and presenting them concisely.

III

Emphasis on Poe

To go back a little, however, available records show that this Columbia College major in Greek and Latin, when he was a sophomore, began to show an accelerated interest in Poe scholarship. (Not being very strong or happy in college, he was drawn to Poe, he later said, because “his writings reflected my mood at the time.”) By the end of 1918 he was conducting a lively correspondence with three Poe scholars of the day — J. H. Whitty, Mary E. Phillips, and Killis Campbell. The Whitty and Phillips relationships soon came to be that of elders to a promising and helpful young student — with Campbell it was one [page 6:] scholar to another from the beginning until the correspondence ended with Campbell’s death in 1937.

On May 22, 1918, at Whitty’s suggestion, TOM applied to Mr. Cole, the librarian of the Huntington Library then in New York City, “to see books relating to Poe,” giving Professor Nelson Macrae, his Latin professor, as reference. His first visit to the Pierpont Morgan Library came before September 29 as the Campbell letters indicate. His meeting with Belle da Costa Greene, to whom he was introduced by the curator of the American Numismatic Society, was one of the more dramatic occasions in the history of his learning to be a scholar. It was at the beginning of his junior year when he came into the library to see the manuscript of Poe’s unpublished play Politian. He looked at it, and talked to Miss Greene, no doubt telling her of the state of his studies and that he was a classics major. I never understood that he made any request to use the manuscript except to collect some variants for Professor Campbell. However, Miss Greene, as he rose to go, in her Belle da Costa voice said, “Mr. Mabbott, I am saving this manuscript for your Ph.D. thesis.” Some kind of a die was cast, but the Campbell letters make it clear that TOM had not yet decided on his future course.

The wind seemed to be blowing in one direction, however. On December 26, 1918, Campbell wrote: “I thank you heartily for your letter of Dec. 22 and for the Politian variants. Every additional variant, every correction, anything that contributes to a better and fuller understanding of Poe is very welcome to me. And a good deal yet remains to be done with Poe. I believe; there is more in the way of bibliography and a good deal more in the way of sources, we can be sure, not to mention matters of biography and of interpretation of text. By all means publish the article of which you spoke, on Poe’s names, plots, and bibliography, otherwise you will assuredly not be treating yourself fairly.”

TOM early in 1918 had begun to be very active indeed, strategically placed as he was in New York City, doing legwork for Miss Phillips in Boston and Mr. Whitty in Richmond. Those two energetic and eccentric workers in the “Poe country,” as Whitty would say, obviously developed a warm emotional attachment to their young helper. Mr. Whitty at this time was planning an edition of Poe’s Tales, and Miss Phillips had long been at work on her Edgar Allan Poe: The Man. They introduced him to dealers so that he could copy and collate manuscripts for them, sent him on journeys, appreciated and encouraged him and, as the letters show, used him mercilessly at times. For [page 7:] those who know the long “Hans Pfaall” manuscript this will seem (as it does to me) an outrageous request. Mr. Whitty’s letter of January 26, 1919, says, “Miss Phillips tells me confidentially of having located in New York a manuscript copy of Hans Phaal [sic]. She speaks of having you make the changes for her and myself — make a most careful copy of the entire MS and go over it a second time to make sure of accuracy, including punctuation.” (Oh, for a Xerox!) These two did much, I think, to further the interest TOM already had in his author, especially Mr. Whitty who as early as May 21, 1918, wrote, “Some day there must be a better and more complete set of Poe’s works; you are young and if you feel like it, persevere; no doubt you may have something to say when that time comes.” Reading the letters, however, one is able to predict very soon that the Campbell association will be the steadfast star in the still somewhat murky skies of TOM’s “Poe country,” to extend Mr. Whitty’s metaphor.

There was still another correspondent, the elder statesman of all Poe country — George Edward Woodberry. Apparently TOM had written a letter to which, on November 8, 1918, Mr. Woodberry replied, saying, “I am very glad to hear of your hopes of being of some service in Poe studies — there is a great deal to do before we shall seem to other nations to have a literature that may fairly claim fellowship with the literature of the world.” The correspondence was not heavy but it continued for ten years through January 1928, two years before Mr. Woodberry’s death. After the two men met in 1922, the exchange became even more cordial and encouraging to the younger scholar, and the last Woodberry letter contains the first reference we have to a new edition of Poe’s works. (The Woodberry-Mabbott correspondence is now in the Houghton Library at Harvard. The Whitty, Phillips, and Campbell letters are in the Thomas Ollive Mabbott Poe Collection at the University of Iowa. The Whitty papers are in Duke University Library; the papers of Miss Phillips are in the Boston Public Library. At present I do not know the whereabouts of the Mabbott letters to Campbell.)

IV

Specialization — Politian

Sometime before he received his AB degree from Columbia in 1920, TOM purchased Harrison’s Complete Works of . . . Poe (1902), [page 8:] and at the same time a change in his handwriting becomes observable. He said afterwards that he deliberately trained himself to write in a small neat hand in order to fit his notes on coin envelopes and on the margins of the Harrison volumes.

On July 15, after the close of TOM’s junior year, Campbell had written, “Your inquiry as to whether you might think of English as offering you a profession interests me very much. As you say, my knowledge of you is mainly of your acquaintance with Poe, but that gives conclusive evidence of your capacity for investigation and your sound understanding of literature. The chances of a field for study and investigation offers exceptional attractions, but the demand for teachers of classics (I regret to say) has grown less and less, if I am not mistaken, as the demand for teachers of English has been steadily increasing. Besides, you are interested in American literature; and Columbia and New York offer a fine opportunity for the study of American literature.”

After the Columbia commencement on June 22, 1920, he wrote thanking TOM for the previously mentioned MLN article, and added, “I am glad to know that you have gone over to the study of English and certainly I envy you the privilege of working with Professor Trent. You will find that as a teacher of English (in case you adopt the profession) your knowledge of Greek and Latin will stand you in very good stead.

“It is fine that you made (ΦΒΚ — and by no means bad that you have a file of the Broadway.”

Graduate work began in the fall of 1920 under Professor Trent. Henry Wells has written of TOM’s admiration for the distinguished scholars he met and how “None stood higher in his esteem nor was held more warmly to his heart than William P. Trent.” (Quoted from a paper by Dr. Henry Wells on Thomas Ollive Mabbott at the Jay B. Hubbell Center for American Literary Historiography at Duke University.) That is true. During his entire graduate career he studied under Trent, helped him carry his books about the campus, as Henry says, and was held almost a member of the Trent family. (In 1927 he traveled to Europe with him.) Teaching, however, leaves few records, and I find little to add to these impressions of an unusually warm student-teacher relationship.

After he received his Master’s degree, Spring 1921, with an essay entitled New Light on Poe, Additional notes on the poems prior to 1831, etc., TOM was ready to take up Miss Greene’s earlier suggestion. He used the Politian manuscript she had “saved” for him as a basis for a [page 9:] doctoral dissertation. He was still collecting, of course, and in 1922 purchased and gave to the New York Public Library (his scholarly alma mater even more than Columbia) a collection of George Eveleth’s letters to Poe. He published these with notes in the NYPL Bulletin, and afterwards as a separate, a copy of which he gave his father as “my first published book.” Killis Campbell wrote him on May 27, 1922: “The reprint of your Eveleth article has come (for which I again wish to express to you my thanks) and a friend has also sent me a copy of your article on Poe in the Lit. Review, which also interested me — and made me envy you, as always, the opportunities you have. It is a pleasure to see you pursuing your studies with so much enthusiasm.”

On August 31, 1922, Campbell wrote: “Your manuscript (of Politian) reached me about a week ago, but I have not been able until yesterday to go over it carefully. . . . I need not tell you that your MS interested me very much. You have succeeded in doing what I should have liked to do — and more than one other editor of Poe, I dare say. I am very glad that the Morgans have at last seen the wisdom of allowing the MS portions of the play to be printed.

“And in my judgment you have done your part well. You ought not to have trouble in finding a publisher.

“I found very little to query or to comment on. And for this I am sorry, for I wanted to be of some help to you. . . . I liked especially your citation of possible classical allusions. Poe knew a good deal more than he is generally given credit for — I am pleased to know that Poe’s Bible has come down to us, and that it is easily accessible.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Whitty’s dream of establishing a Poe Society had borne fruit in the Edgar Allan Poe Shrine at Richmond. TOM, reading an unpublished poem, George Edward Woodberry, and James Southall Wilson all had a part in the opening program on April 26, 1922. Mr. Whitty in his letters had several times said that if Politian had trouble finding a publisher, perhaps the Shrine would have a press and make it the first publication. Politian did have trouble, having been refused by Yale and others, but it was being printed by George Banta in Wisconsin. Finally, in the spring and summer of 1923, the Poe Shrine “published” and distributed the book. The edition of Poe’s unpublished play made TOM known at home and abroad (there was a French translation in 1926). [page 10:]

V

A Diary of Poe Activities — 1924

The Poe and Whitman Seminar at the University of Chicago in the summer of 1923 showed TOM not only that he could teach but that he loved teaching. It was two years, however, before he obtained a teaching post, and he spent 1923-1925 at Columbia directing one of the sections of the Master’s Programs. One gets some idea of his Poe activities at this time by reading excerpts from a series of long, literary letters he wrote during the year 1924 (to MCM to whom he had become engaged in August 1923).

————————————

December 10, 1923

Speaking of this very favorite topic (books), you will like to know that this week I obtained a full file of The Aristidean, a New York magazine of 1845, of which I never could locate but three numbers before. Not only has it three new reviews (only 2 are new really) by Poe, but contains four unknown stories by Walt Whitman (about 26,000 words in all) — its rarity being so great that nobody ever seems to have searched a copy since Walt became famous. [The copy is now in the Rare Book Division of the New York Public Library.]

————————————

January 16, 1924

There is little news — I am at work mentally on the Poe eulogy, am drafting it — only the outline is yet written, but slowly it is taking shape in my mind. I shall start Friday or at any rate, D. v. Saturday, and expect to stay over until Sunday morning at Baltimore. [He was to deliver the birthday address at the Poe Society on January 19.]

————————————

January 21, 1924

The night I reached Baltimore I shut myself off from visitors — wrote one or two notes — and then worked a little on my speech. The next morning I got in touch with Prof. French of Johns Hopkins who took me to the Homewood Club for lunch where I met several of the local celebrities — then we proceeded to the meeting. The Saturday papers carried only the bare announcements of time and place, but the clipping accompanying this letter shows that we were written up “in flamin’ style” as Artemis Ward wanted his handbills, and the account [page 11:] which is the work of a Greek instructor, who combines journalism & classics, being inspired, is pretty accurate, save that I called Poe “the foremost lyric poet, the foremost literary genius of this New World,” meaning America & the printed version dropped the “new.” The truth is, in Baltimore, the printed version is not overmuch criticized — at any rate the sentiment seemed to be that a eulogy was wanted, and you know how highly honored I felt to be able to deliver it.

We held the exercises in the church — I was the sole “speaker” — the others read or recited, etc. — & I came last. On the whole my speech went pretty well — the newspaper report was prepared from an abridged draft of my speech & omits some heads — especially that I gave a little discourse on the text “Death is swallowed up in Victory,” and my last figure where, commenting on Poe’s line, “Our flowers are merely flowers,” I concluded: “I feel, in Tennyson’s words, I ‘but cast at his feet one flower that fades away but that his pure and musical poems are indeed the brilliant and immortal flowers of paradise’.”

After the ceremonies I went out with Dr. French and the school-children — Dr. French is the bearded gentleman behind me — the lady by my side is the girl who presented the wreath on behalf of the children — the old gentleman in the lower left hand corner, bareheaded, is Mr. Brough, principal of the Edgar Allan Poe School. Then came the handshaking — several people whom I knew were present — a Mrs. Clemm, relative of Poe’s wife’s father, was among those who thanked me, and Miss Reese, the poet, also. There is a good deal of detail that must be omitted, but do not think I took all this in a light-hearted spirit — but I know Poe would have liked what I said — and what more could we ask.

Dr. French drove me out to his home, where we had dinner with Prof. Bright (head of the Dept. of English) and talked afterwards.

Part of my Griswold edition of Poe’s Works, Mr. Whitty’s Xmas gift to me, now reposes between your bronze book-ends.

————————————

January 25, 1924

I have had several interviews with pupils, and in addition expect to go up to Charles Bopes’ home and talk to a small group of the poetical on Poe’s theories of poetry. A letter from Mr. H. H. Ewers, a German writer, came to-day with request for permission to translate Politian — which I shall of course grant free — owing to the financial condition of the Germans one cannot ask for money, & indeed while practical enough [page 12:] otherwise I have no great desire to make money out of Poe. If it comes, all right — if not, it is at least a service to literature.

————————————

January 28, 1924

Yesterday I read Mr. Sadakichi Hartman’s Confucius, a very curious book, which amazes one by its depth. His book has crudities — ugly things of an extraordinary ugliness, but I have written him a rather enthusiastic letter, thanking him for the book, and expressing my pleasure in receiving it. I believe he admires Poe & for that reason sent Poe’s editor his book.

————————————

January 30, 1924

I must confess that during my college years, the assigned work was done because it was assigned — but there was the “outside” reading, then came Poe, and his little-read contemporaries, who led me into a new world of “flowers & fruit and sunshine” — a paradise of the Arabian Nights, wherein I could forget my surroundings.

I have been busy — students in the morning, one with a rather interesting essay on the contemporary criticism of Hawthorne. And besides that I had to examine a Poe MS in a sale. It is the opportunity to see Poe MSS, etc., in sales that is perhaps one of the chief advantages of New York to a scholar — the present one makes more complex the whole relation of Poe’s Literati text to that of Griswold’s. That G. botched the job is certain anyway. A friend in Baltimore sent me Miss Reese’s little volume, Wild Cherry — mildly elegiac, all, or almost all, a trifle melancholy. I liked two or three very much, but found no hidden Sappho. There is within me a sort of thirst for “supernal beauty,” for “more than mortal melodies” — how rarely do we find them! I, too, am almost intoxicated by the highest poetry & the power to carry me away I recognize as the secret and masonic sign of great verse.

————————————

February 1, 1924

It makes me very happy that you do well in Greek, of all subjects the most respected by me. Thank goodness I never had exams in some of my graduate courses, and that Poe was there to help me with some of the others.

Yesterday came a letter from Mr. Woodberry with his congratulations — it is an honor to know him. I feel it more every time I hear from him, and often look forward to your meeting him. I am reading Miss [page 13:] Wyman’s Ph.D. thesis on Seba Smith and Elizabeth Oakes-Smith just now, and in general am kept quite busy.

————————————

February 4, 1924

Of news I have very little — save that I am busy — pupils part of the time, and Poe the rest so that I progress rather slowly with Pope’s Iliad — which does not possess for me the charm of novelty.

————————————

February 6, 1924

I went last night to the Charity Ball, a very old traditional affair. Though I am not a great one for balls and dancing, the Charity is with our family a custom.

This afternoon I went to the Pierpont Morgan Library and was at work on a Poe MS — a draft of his Living Writers of America, a work never finished which I believe I can get into some kind of shape for ultimate publication. I also read a series of letters identifying Poe as the writer of a good many Southern Literary Messenger criticisms hitherto doubtful.

————————————

February 9, 1924

Have bought me two black letter quartos — The History of Parismus, Prince of Bohemia, and The Seven Champions of Christendom.

————————————

February 11, 1924

I had a letter today from a Capt. Pleadwell who hopes to do a good bit on Pinkney, the Baltimore poet I admire. There is a great need for a new edition. I am trying to get up steam to start bothering publishers over my new Walt Whitman stories — which make a rather nice small book, but the fools who rejected Politian have so set me against publishers that I am really little of a mind to dicker again with them.

————————————

February 13, 1924

Monday’s opera was Romeo and Juliet — it is pretty, but the version makes one think of a little chap-book reproduction of Robinson Crusoe when compared with the tremendous poem of Shakespeare. As you are thinking of taking a composition course, it may not be amiss to point out that the above is a bad simile, since the reader may not have seen a chap-book.

Yesterday we had a great meeting of the Editorial Board of the Columbia edition of Milton, and Prof. Trent is starting the thing off with [page 14:] a will. We want to do a really fine piece of work on it, and the project seems to be very ambitious in every way. One feature concerns me intimately — master’s essays are to be written in connection with certain problems, and I hope to have charge of them.

My work on the Poe MS may be published separately or may not, but has to be done up the same way in either case. I am trying to get my Whitman stories off my hands — sometimes I meet people who say “How do you find research to do?” — with me it almost seems I find too much.

————————————

February 15, 1924

Last night I was in the office of the Berkeley where my aunt lives when “Mr. Mencken” came in — I took a chance that it was H. L. Mencken, & since Poe’s editor can do what Dr. Mabbott might hesitate to do, I introduced myself & had a five minute talk with him — a most energetic person, attractive in some ways, not so in all, perhaps. He said Politian should have found a publisher, and asked me to let him know more of my Whitman stories. Of course nothing may come of this, but it is interesting to meet these famous people.

————————————

February 20, 1924

This is an extremely stormy morning and what with my cold I called up Columbia — and did not go up to the old place. But it looks like a busy day despite that, for I have an essay to read, and parts of a Ph.D. thesis to look over (dealing with early magazines), and last, but by no means least, the New York Public Library called me on the ’phone to say they had just acquired Poe’s “Thou Art the Man!” which they want me to look over, so you see it is a good thing sometimes to be in New York, even though the climate is not all one would wish.

————————————

February 23, 1924

My own work is mostly in the M. A. business, and not worth reporting — though my interest in Pinkney has brought me in touch with Capt. Pleadwell (with whom I plan an edition of the poems, and we are after a publisher) whom I, just from his letters, presume to be a man, and whom I hope to meet in March. Your Miss [Edith] Rickert is one of the two most competent women in the learned line I ever met — the other is Belle Greene — and I should judge her Chaucer course must be interesting. [page 15:]

————————————

February 25, 1924

Work is going on at Columbia rather nicely — one of my students has found two new poems of Adelaide Crapsey (a modern of whom I know little) and I was greatly pleased that my advice on methods with a recent subject turned out to be useful. My own work on E. C. Pinkney has been quite exciting — I have located some MSS of the poet at Yale, so feel I can rightly share with Capt. Pleadwell in the enterprise, and am now going looking for more. Of course these things do not excite the layman, but to the lover of research provide a decided thrill of delight.

————————————

February 27, 1924

My students are of course in the midst of work now and I usually have several interviews every morning, and have good hopes of most of them — they are bringing in facts every once in a while for “my Poe.” All sorts of things turn up, and I add a new note every little while. The NYPL Bulletin I shall send on when it comes out — I presume in a very few days. My note on “Thou Art the Man!” covers three pages and will be illustrated with three facsimiles of portions of the manuscript.

Pinkney is the thing most on my mind now — minor figure as he is, there is a certain charm about some of his lines that quite enchants me.

————————————

March 6, 1924

I found Izaak Walton interesting even in the technical passages, though I know nothing of fishing; but I remember that one of the books I have most enjoyed reading, ever, was a Catalogue (with copious notes) of a Collection of Chinese Porcelains, which took me quite into another world — and I am like Alexander in one respect, even before conquering one world! This is an involved simile, Classical in nature, quite in the Pinkney manner — and brings me to my Yale trip, which proved very interesting. I found the poet’s album to be very important — it contained, among other things, a printed broadside, Carrier’s Address, written for his paper and at least two fragmentary poems, both Byronic — “The Immortal” and “Cornelius Agrippa.” All this is fish to my net, and should prove interesting to students.

————————————

March 12, 1924

There is little news. Capt. Pleadwell is to be in town Friday night to Monday morning and we shall probably be busy with Pinkney matters a good part of the time. I had lunch today with one of my students — a very enthusiastic young man who rather did my heart good — a healthy [page 16:] mind, though not conspicuous for intellectual powers of the highest sort, yet given to thinking.

————————————

March 19, 1924

I am very busy with many things; and a great many essays (really too many) have been coming in to be read. Some give fair promise of being excellent. One, which I have already read, is written with such spirit that I was carried past my station in the train finishing it. Pinkney progresses rapidly although no publisher has been approached yet.

————————————

March 31, 1924

Do you remember my telling you of getting a rare magazine with uncollected articles by Poe and Whitman in it? Well, last night came a check for the article on “Walt Whitman and The Aristidean” which I have written for The American Mercury — this article brought $24.00, just what the original file of the magazine cost me, but I hope the edition of the stories will bring in a bit more.

————————————

April 12, 1924

Yes, textual work is fascinating though not to some quacks (a genus that includes a good many teachers of literature) and probably I have more sympathy with scientific methods than most literary people. I have always felt a great many facts were needed to form even a few good opinions — had I any mechanical skill, I might have become a scientist anyway!

————————————

April 29, 1924

The Poe Shrine asked me to bid for them certain items — giving such ridiculous bids that I knew they would get nothing, and yet what could I do but go to the sale. Prices were tremendous — the dedication copy of Poe’s Raven and Other Poems with his inscription to Elizabeth Barrett Browning brought $4200 — his own copy of Eureka with autograph corrections brought $4200. This latter pleased me, as I have an earlier copy of Eureka with several autograph corrections, which I reckon ought to be worth $500 to $1000 — though I picked it up for very little a year or so ago, and have no desire to sell it! I got the N. Y. Mirror, 3 vols, with a good many Poe contributions in it for $20, just about what it was worth, and as I really needed a set, and have waited five years for a chance to buy one, I was not ill-pleased. It is necessary in my work of discovering just what Poe wrote to have easy access to the papers for which he wrote anonymously. [page 17:]

————————————

May 6, 1924

My lecture to the extension AM. LIT. Class in Columbia went off very nicely, yesterday — and I am to address the AM. LIT. course at N. Y. U. this evening. I ought to have my own course, as you know, and can only bide my time. Well, perhaps it will come!

————————————

May 12, 1924

“A Poe Manuscript” is a very technical article, but I’ll send on a separate. I spent this morning collating a volume with E. A. P.’s manuscript notes, and feel rather dull. I want to read some of the Chatterton Rowley poems, for some reason — perhaps because of their objectivity, a quality T. C. has in a degree only less than Shakespeare. My Whitman article is due in the June Mercury — it is only two and a half pages, I think. Do you see Mencken’s Americana articles — not on Americana such as I collect, but very stimulating to a consideration of our present culture in this country.

————————————

May 21, 1924

Today we had the master’s exam at Columbia. Afterwards I came downtown again, and have spent the afternoon partly in the N. Y. P. L. trying to find out a number of things, and accomplishing very little. Last night I read most of Moore’s Irish Melodies, and the first two acts of Shakespeare’s Pericles which I mean to finish this evening — then to The Two Noble Kinsmen which I have never gone through. It is not easy to keep up one’s reading without any encouragement, but I do what I can, and wait until I can give my own courses, as so many lesser men do daily.

————————————

May 24, 1924

Today I went to the N. Y. Historical Society and there found my friend Pinkney was mixed up in a couple of duels of which we had not known anything before — then in the afternoon to a show called Innocent Eyes which I confess to have enjoyed very much, though the intellectual qualities are nil.

————————————

September 12, 1924

My German translator is trying to get an Italian publisher for my Politian. Isn’t that good’? There’s no money in it, but it spreads one’s reputation. [page 18:]

————————————

October 19, 1924

I am beginning to read Boswell’s Life of Johnson which I have had in the front row of my bookcase for some years untouched. It is a fascinating work, which I should have read, but you know how it is with busy men! In the Life of Pinkney I said of the poet, “He had too little business to allow the proper enjoyment of his leisure” or words to that effect. As you are not to see that work in MS I might as well quote myself now! Really it is a strange and learned book that I plan, and I have grave doubts about its appeal to a commercial publisher. But Prof. Trent and I are unwilling to produce an unscholarly book, and I don’t see how one can understand Pinkney without footnotes.

————————————

October 21, 1924

Today I looked at the MS of an Essay by someone in Litchfield, Illinois, who thought a mass of undigested notes an essay; I rode in the Park a while; I read a little in my newly acquired six issues of The Colorado Weekly Times (Central City 1867) and examined the Photostats of Pinkney’s prose which at length came to hand. Tonight I have seen the old gentleman [Trent], read a few pages of Boswell, and now write to you before doing a little more letter writing and work on the book.

————————————

November 10, 1924

The excitement here is over the Year Book of the New York Poetry Group of which Bopes and I and Lucia Trent are members, and Mrs. Percy the leading spirit. They have taken it into their heads to print a fifty-page volume with about three pages from each member — and I was picked out (or shall we say picked on) to help select the poems, and to act as general editor, and to contribute a poem or two. I am no poet but found two things, “Sonnet to the Memory of Thomas Dunn English,” and a poem on “The Ruins of Troy.” The first has been published.

Today Prof. Trent is 62 years old.

————————————

November 13, 1924

Today I went to an auction sale, and bought six early (that is 18th Century) chap-books very cheap — two of them Philadelphia imprints, and I imagine rare and valuable.

I want to leave New York early Tuesday and have a few hours in the Library of Congress at Washington on my way [to Chicago]. I would [page 19:] like to see the Boston Flag of Our Union for 1848 which may have anonymous Poe contributions as well as signed ones.

————————————

November 20, 1924

Yes, New York keeps busy — yesterday I chanced on a Colonial book, L’Estrange’s Josephus, N. Y. 1775, vol. 3 only, no other copy located, which I obtained for a quarter. I mention such things to you since they stand out in my memory — and the only other things perhaps worth chronicling can be talked to when we meet. The chief one is the Poe Work, which I am getting after once more, and the various ramifications of it, but enough for the present.

————————————

December 27, 1924

As to the MLA I hardly figure to cut much of a figure there — a prophet is not without honor, etc. — and my ten-minute paper I hope to write this evening. — Yesterday came a nice letter from our “next President” (Charles Dawes) in response to some queries I sent him about the poet Rufus Dawes who knew Pinkney. I’ll show it to you sometime — I wish I could get in a position of some importance myself someday — perhaps we shall live to see it!

————————————

VI

The Summing Up

TOM was obliged to spend a second year (1924-1925) directing Masters’ theses at Columbia, but in the fall of 1925 he was called to an assistant professorship at Northwestern University. He stayed for three years, and while he was there Macmillan published Life and Works of Edward Coote Pinkney by Pleadwell and Mabbott (1926), and the Columbia University Press brought out a regular and a deluxe edition of his Half-Breed and Other Stories by Walt Whitman (1927).

Living in Evanston he missed his New York coin and book dealers and, stimulated by Pleadwell’s purchase of a leaf of the Gutenberg Bible, he began to collect early fifteenth-century prints directly from European dealers. As he had hinted in his letter of March 6, 1924, he was “like Alexander in one respect,” and the history of early printing was another world to conquer. As in his beginning Poe studies, he soon approached the chief authority in the field, Professor W. L. Schrieber of [page 20:] Potsdam, Germany, who at that time was adding to and revising his great Handbuch.

By 1927 TOM was helping the old gentleman in this project. In that summer he made his first trip to Europe in company with, and as a kind of assistant to, Professor Trent, who was traveling with his daughter Lucia. The men spent a good deal of time, on the boat at least, going over problems, translations of Latin, etc. of the Columbia edition of Milton. While the others went on to Paris where he would follow later, TOM stayed on in England and guided the visiting Professor Shreiber through the difficulties of the English language, and helped him search out and measure uncatalogued prints at Oxford and elsewhere. More pertinent to the Poe story is his meeting with George Edward Saintsbury, 82. On August 17, 1927 he wrote from the Hotel Russell, “I am due to lunch with Saintsbury tomorrow and with Campbell Dodgson, the B. M. Curator, Friday.” He later wrote that the distinguished critic had said, “Poe and Whitman are the Jachin and Boaz (II Chronicles 3:17) of American Literature.” Saintsbury became a regular correspondent — he did not die until 1933 — reviewed TOM’s Selected Poems of Poe (Macmillan, 1928), and at TOM’s request wrote an introduction to Poe’s Criticism for the proposed edition. It was the Mabbott approach (perhaps that of all scholars) to be working on all Poe phases at once. He had early decided that the Poems would lead off the edition, but one would hardly have known it from his activity on the Marginalia, Tales, Criticisms, [[and]] Letters.

Returning home from abroad TOM began his third year of teaching at Northwestern. He was elected most popular professor but nevertheless decided to move on to Brown University in 1928 (just after his marriage in August), and then to Hunter College in 1929, in an effort to get release from teaching freshman composition classes (like using a razor blade to open tin cans, he said). Because of various pressures Hunter’s promise of such freedom had to be revoked, but now, at least, he was in New York, at home again with the New-York Historical Society, the NYPL, the American Numismatic Society, coin and book auctions, musical plays, and old friends.

TOM spent the major part of the rest of his life teaching the undergraduates in the unusually heavy program of a city college, but he never ceased working, as time permitted, on his two hobbies: the collection of coins and the gathering of materials for an edition of Poe’s Works. Woodberry’s last letter of January 5, 1928, refers to “The [page 21:] Columbia edition,” but the earliest formal notice I have in my files of a Mabbott edition is in a letter from James Southall Wilson, dated February 2, 1928, on the letterhead of the Virginia Quarterly, the University of Virginia: “First let me say that your edition of Poe has my sympathetic interest and good wishes . . . and willingness to aid you in any way that I can.”

A Mabbott edition of Poe even as a hobby, however, was to have many interruptions. The first came when Professor Trent (in 1924) asked him to join the editors of the Columbia Milton, with the understanding that after Milton the Columbia Press would address itself to an edition of Poe’s works. TOM enjoyed his work on Milton and received a good deal of praise for it. For a time he was certainly counting on Columbia for his Poe. In the introduction to The Doings of Gotham (1929) TOM says “. . . the references will also serve as a guide to the fuller projected Columbia University Press edition of Poe, where I hope to arrange the nonimaginative prose by place and date of publication.” In the end the great expense of producing the Milton and, I imagine, the unfinished state of the Poe, changed the circumstances for the Press. There was to be no Columbia Poe. Some of the early buoyancy and easy successes were over, but not the dedication to the work. TOM at this time made the decision to go forward, at his own pace and at his own expense, collecting materials for an edition of the works of Poe. The production of such a work was bound to be expensive and for a long time it appeared that no publisher would venture to undertake it. I will not proceed further in this account which I have limited to TOM’s early work on Poe, except to speak of two abiding characteristics that he had from the beginning and that deepened and continued as his work progressed.

It was a scholar’s duty, he said, to add to knowledge, not to hoard but to share. Younger and older workers have testified to his generosity. I would like to speak especially of Arthur Hobson Quinn. During the writing of the Life of Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (1941), the Mabbotts visited the Quinns near Philadelphia, and were made to feel at home in their closely knit, loving household, as comfortably Victorian in its furnishings as Grandfather Ollive’s house had been. In return Mr. Quinn spent several days in our small New York apartment while he and TOM searched out every spot in the city where Poe had lived or frequented. [page 22:]

There was a great exchange of information and confidence between the older and the younger scholars, and for years I have cherished in my memory something Mr. Quinn said to me — that TOM was the most generous scholar he had ever known. It is pleasant now, thirty-seven years later, to rediscover in our files a letter that expresses the gratitude of one generous-hearted man to another. Dated October 29, 1941, from the English Language and Literature Department of the University of Pennsylvania, the letter is as follows: “My dear Mabbott: I am sending you today one of the earliest of the autographed copies of the Poe book. I can hardly express adequately my gratitude to you for your help with it. You are in a real sense a collaborator in what I hope will be the definitive biography. Very sincerely yours, Arthur H. Quinn.”

Throughout his career TOM’s generosity to students and learned institutions (to whom he judiciously distributed many of the documents he had collected) never wavered. Only one other characteristic of his life as a scholar was as consistently adhered to: the emphasis in his early work on sources and records rather than on his own opinions was maintained to the end. He was never out to Mabbottize Poe. He said once that perhaps the advantage he had as a Poe scholar was that he had started out so young. He had never felt that he knew more than his author, and in all his vast accumulation of Poe’s sources, influences, “borrowings,” he never lost sight of the genius at the center. “Like Shakespeare and Moliere Poe took his own where he found it, and unfailingly improved upon his sources.” (Mabbott, The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, I, xxix.)

EPILOGUE

————————————

Favorite Poe Poem

You ask what is my favorite Poe poem. Such a question always brings an emotional answer from me, and my choice is “Eldorado,” though I do not rank it first among his poems. It is Poe’s comment on the California gold rush of 1849, where many who sought treasure found death. The attitude of facing life boldly is something more often thought of as Browning’s than Poe’s, but Poe’s most admirable quality was his gallant devotion to literature “in sunshine and in shadow.” That last stanza is as heartening as anything I know.

TOM letter, written July 6, 1924.

————————————

ELDORADO

Gaily bedight,

A gallant knight,

In sunshine and in shadow,

Had journeyed long,

Singing a song,

In search of Eldorado.

But he grew old —

This knight so bold —

And o’er his heart a shadow

Fell as he found

No spot of ground

That looked like Eldorado.

And, as his strength

Failed him at length.

He met a pilgrim shadow —

“Shadow,” said he,

“Where can it be —

This land of Eldorado?”

“Over the Mountains

Of the Moon

Down the Valley of the Shadow

Ride, boldly ride,”

The shade replied, —

“If you seek for Eldorado.”

— Edgar Allan Poe

APPENDIX

————————————

A talk presented before the Poe group of the Modern Language Association on December 29, 1978, by Maureen C. Mabbott [page 26:]

————————————

TOM’s first choice for college had been Oxford University, but his close, protective family had vetoed even his second choice, Harvard University, in favor of Columbia where he could live at home. It was, then, with some pride that he received (after other University Presses had backed off because of the great expense) a delegation from Harvard University Press, in the persons of Thomas J. Wilson and Kenneth B. Murdock, asking for his edition of Poe. He was not, however, to be one of the really long-lived members of his family as he had confidently expected, and Volume I of his Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, the Poems (1969), carried an explanatory paragraph:

At the time of Mr. Mabbott’s death on May 15, 1968, the present volume was all but finished. The printer’s copy for the texts of the poems and for the accompanying apparatus had been read and approved by him. He had completed recent revisions of the preface and the introduction to the poems, of all the appendices, and of the “Annals,” as he called his outline of Poe’s biography and career as a writer. He had also corrected ninety-five galleys — more than half — of the proofs of the poems and commentary.

This edition of the poems has been seen through the press by Maureen C. Mabbott, who served as assistant to her husband during the many years of his research, and by Eleanor D. Kewer, Chief Editor for Special Projects of the Harvard University Press. Both have been fully cognizant of Mr. Mabbott’s methods of work, and their final efforts loyally and expertly carry out his wishes.

Clarence Gohdes

Rollo G. Silver

November 1968

It was May 1978 before Volumes II and III, the Tales and Sketches, were published. On December 29 of that year at the annual meeting of the Poe Studies Association, chaired by Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV, I discussed some of the problems of

Seeing Poe’s Tales and Sketches through the Press

At the time of my husband’s death in May 1968, Harvard’s Belknap Press still had work to do to get Volume I between covers — in fact it was a year before it was published. In the meantime the Press had [page 27:] received in its editorial offices the boxes containing the typescripts of TOM’s edition of Poe’s ninety-odd Tales and Sketches. During that time also it had been decided that Harvard’s Chief Editor in Charge of Special Projects, Eleanor Kewer, and I would undertake to see this mass of material through the press. We were both amateurs in Poe scholarship, but Mrs. Kewer would be able to draw on her long experience as Harvard’s chief literary editor. She had also been press editor for Volume I which contained all of Poe’s poems and a short, informative life of the author.

My qualifications were different. I had not done scholarship on Poe, but I had lived in the house with him for forty years. My husband was a man of many interests, and in a way Poe was a background figure in our lives, but he was always there.

I was familiar with the Mabbott aims for the edition, with its problems and materials, and with the personalities in Poe scholarship, all of which we had discussed and considered together for many years. The work had been singlehanded from the beginning — there were no collaborators, no grantors, no committees to be consulted. If the Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe was to follow the Mabbott vision for it, as the Press and the advisers were determined it should, I was in a position to make his wishes clear.

One of his directives made our work possible — and that was his wish to emphasize records and sources and not his own opinions. Under these circumstances, although neither Mrs. Kewer nor I could give our full time to the work, we felt we could see the Tales through the press with the advisory resource for which TOM had provided.

I

After we had completed the index and other final details of Volume I, we were ready to begin. The whole plan of the edition had been carefully worked through in the production of Volume I, but there had been no time to settle details that would come up for the first time in the Tales. The chief problem, we early came to realize, in making available to the general public the results of TOM’s life-long study and meditation on the life and works of Poe, was one that would have been a problem to him, too. How does one describe a long familiar face, how does one make clear to a stranger the many facets of a complex genius with whom one has lived for fifty years? The familiarity itself led to ellipses, to [page 28:] assumptions of knowledge on the part of the readers, that had to be cleared up.

TOM himself, as I have indicated, would have had to enlarge and elucidate some of his notes, but for him it would have been easier. The storehouse of his memory would not have been locked as it was for us. A question he could have answered in short order we had to approach often in a roundabout way and at great length simply because we knew no better. The source material for these volumes is multitudinous, scattered and, in a few cases, lost. It was a great blow and rather demoralizing, to discover, among other things, that the unique file of the Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper had been missing for several years, and that the Monck Mason pamphlet on the Ellipsoidal Balloon had disappeared from the lone American library where it had been at the time of the original research.

II

In addition to filling in lacunae in the typescript there was also the matter of errors. When we found in the first 200 pages as many as three errors, we knew that for a work like this we had to undertake the massive job of checking every reference once again. This we felt compelled to do in spite of TOM’s fine record for accuracy — too much time had passed, the material had been copied too often. And it was not a simple check by another authority, either. We early learned that if TOM’s data disagreed with that of someone else, we had better check again — new evidence was probably in his notes somewhere. But we could not rest, as we were tempted to do, in the feeling that he was bound to be right.

Consider the case of the forged signature. In an early note in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” the transcript carried a statement that the Berg Collection had a copy of Hoyle’s Complete Games with Poe’s autograph signature. At first the officials there could not find any copy of Hoyle’s Games in the Collection. I was persistent and asked Mrs. Szladits to make a personal search. Always cooperative, she did so. She found the book and the signature, but not under Poe proper. She found a box labelled “Poe Forgeries,” and in it, among other items, was a small pocket Hoyle with “Edgar A. Poe” written on the flyleaf. When I asked her who had decided the signature was a forgery, she said, “Our Poe expert, Tom Mabbott.” If he had been the one to cast his eyes on the statement in the typescript, he could have straightened it out immediately. [page 29:] Because he was not working with us, we were constantly subject to frustration and delay.

III

Among the many smaller problems, we had three large tasks in preparing the Tales typescript for the printer. I have spoken of two of them. First, the filling in of lacunae — here the edition was fortunate indeed, in that Eleanor Kewer has a genius for perceiving what the uninformed reader will need for a just comprehension of the subject. Second, as I have just stated, came the checking of the references and notes in the ninety-odd tales. The third task had to do with texts and variants. The London Times Literary Supplement said, in a review of Volume I, Poems, that the edition carried the authority of having been done by the one man best equipped to do it. Whatever the merits or demerits of this circumstance, it continued for Tales and Sketches. The work on the texts had not been done by a committee formed for the purpose and federally or institutionally funded, but privately “by the one man best equipped to do it.” TOM’s whole life-pattern of research was a part of his equipment. First recognized by his fellow numismatists, he had early shown a remarkable feeling for authenticity. This talent, more intuitive than learned, was formed and developed by being constantly with the subject, first with ancient coins, and then with Poe manuscripts, texts, and life studies. It was from this long background of study and proven “rightness” that he made the decision not to follow for his Poe texts the Greg-Bowers textual methodology.

About general policy and procedure, therefore, there was no question — we followed the schedules worked out by TOM, and approved by the Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press. For details and specific advice, however, we leaned heavily on the two men TOM had empowered to look after the interests of the edition if he could not — Clarence Gohdes and Rollo Silver. When I speak of advisers, I refer to them. As Silver was in Boston Mrs. Kewer and I could, and did, consult him in person, especially about matters of style and presentation. Because I had to consult Gohdes by means of letters, it is in correspondence with him that I have a more complete record of some of the problems that beset us.

The texts of Poe’s Tales were at this time all housed in the Mabbott apartment (in the original magazines or in photostats of the manuscripts, [page 30:] and newspapers), and thus it fell to my lot to “take care of the variants,” with Eleanor Kewer advising and Patricia Clyne helping with the reading, checking, and comparing. An indispensable editorial assistant, as well as typist and proofreader for all the volumes, Patricia Edwards Clyne had been a student of my husband at Hunter College. For a number of years she had been his aide and confidante. Her friendship and dedication to his work was the best inheritance he left to me.

TOM’s plan was to present complete verbal variants for all the authorized texts of the tales, and concern with these texts had been his first concern. At the very beginning of his work he was reading and recording from original manuscripts in auction houses and libraries, and from magazines he had begun to collect while in college. He had the variants all recorded and they were included in the Tales typescripts. He had rejected the Harrison plan of line references at the back of the volumes in favor of paragraph references he had worked out. (For the general reader this was, no doubt, an annoyance but from the first TOM had insisted that the scholar was to have on the page before him not only the copy-text but also all the authorized variants from it.) But the final plan of presenting the prose variants had never been discussed with the Press. When it was, the decision was made that small superscripts would be better than TOM’s paragraph plan. In other words the variants had to be restated. This meant long hours of comparing and reviewing all the original texts — and visiting manuscripts again because, as we found, so-called facsimiles even could not be trusted. (See the discussion under “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Mabbott II, 527). But at least no change of policy was involved. That necessity soon appeared, however. I can explain best by quoting from a letter I wrote to Clarence Gohdes after Mrs. Kewer and I had discussed it with Rollo Silver.

I quote:

Tom, who chose the text of each tale on its individual merits, ends up by using more texts from Griswold’s Works of Poe, leaning as heavily on them as Harrison had on the texts of the Broadway Journal. He gives his reasons (most important, author’s changes), but in one area we feel he has not sufficiently backed up his choices. Stewart (Harrison, II, 299) says “Griswold is very defective in typography.” In the margin of his copy of Harrison, opposite this statement, Tom has written “Not so!” but does not elaborate on this anywhere. In view of the public assumption that because Griswold was unreliable and vindictive in some cases, he must be in all (Stewart’s remarks in 1902, and Edmund Wilson, Fruits of the MLA, 1968), we feel Tom’s case needs more visible evidence than he presents. It is evident from his notes that he did not intend to record every typographical error. He is, of course, correct in his “Not so!” A close comparison of the texts where Harrison uses the Broadway Journal and Mabbott the Griswold texts [page 31:] reveals that the typographical errors in the Broadway Journal add up to 129, and those in Griswold to 93. How else are we to present the evidence except by recording every misprint? Actually it will not clutter up the variants very much. Would you give your approval to such inclusion?

I fear we will be criticized for recording every typographical error — once started on this path one has to continue, and misprints in other texts must be recorded too. I would like your opinion on this.

The Gohdes answer pleased us. It was clear and to the point: “I am of the belief that every misprint should be recorded, and all variants,” and he went on to say:

I remember that Tom in his “Annals” mentioned his belief that Griswold had been too maligned — and I am thus interested in the evidence you provide in your ‘Comparison’.

In Volumes II and III of the Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, the Tales and Sketches, the misprints are recorded along with the variants. Anyone curious enough to do his own counting can see for himself what and where they are. It was indeed false to say that the texts in Griswold’s Works (that is, in the first printing; see Mabbott III, 1399-1400, for a discussion of Griswold’s texts) are full of typographical errors, and TOM was right in his cryptic “Not so!,” but we spent a great deal of time compiling the evidence to prove him right.

IV

This has been a “tip of the iceberg” account of some of our experiences in seeing Poe’s Tales and Sketches through the press. If I have indicated that there was a good deal of work, that is correct, and, as we state in Acknowledgments in Volume II, we are indebted to a number of very generous people. But it would be incorrect for me to leave the impression that we have managed to present TOM’s edition of Tales and Sketches complete and without error. I am sure that is not so. There are errors to be corrected, work to do, and younger scholars to do it.

And in saying that, I want to end with a salute to Harvard University Press and to the Chief Editor in Charge of Special Projects who terminated her professional career as assisting editor of Poe’s Tales and Sketches. My husband never lived to see in print any of the edition that was his almost life-long concern. I do feel, though, that the first three volumes of the Collected Works of . . . Poe, published since his death, bear the Mabbott signature, clearly and without deflection. And that is because of Eleanor Kewer, and the backing she received from the Press. [page 32:] She had a respect for, and a protectiveness about the statements, opinions, and conclusions of her author that was equal if not superior to mine to whom it was my life’s concern. She often illuminated, she never shadowed or changed any of his avenues of approach. She was careful to preserve not only his ideas, but even his ways of expression, eccentric as they sometimes were. I wish all authors such an editor, and such beautiful volumes, as the Belknap Press has produced in Poe’s Tales and Sketches.

Informal List of Books Published by

THOMAS OLLIVE MABBOTT

The Letters of George W. Eveleth to Edgar Allan Poe. ed. by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. The New York Public Library, 1922. The copy in the Poe Collection at the University of Iowa is inscribed “To my father, this copy of my first book.”

Politian; an unfinished tragedy, by Edgar A. Poe, including the hitherto unpublished scenes from the original manuscript in the Pierpont Morgan Library, now first edited with notes and a commentary by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. Richmond, The Edgar Allan Poe Shrine, 1923.

An Unwritten Drama of Lord Byron, by Washington Irving; with an introduction by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. Metuchen, N. J. C. F. Heartman, 1925[[.]]

The Life and Works of Edward Coote Pinkney; a memoir and complete text of his poems and literary prose, including much never before published, prepared by Thomas Ollive Mabbott and Frank Lester Pleadwell. New York, The Macmillan Company, 1926.

Poe’s Brother, the poems of William Henry Leonard Poe, elder brother of Edgar Allan Poe, together with a short account of his tragic life, an early romance of Edgar Allan Poe and some hitherto unknown incidents in the lives of the two Poe brothers . . . with a preface, introduction, comment and facsimiles of new Poe documents, by Hervey Allen and Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, George H. Doran Company, 1926.

The Half-Breed and Other Stories, by Walt Whitman; now first collected by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. Woodcuts by Alun Lewis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1927.

Selected Poems of Edgar Allan Poe, edited with introduction and notes by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. Macmillan, 1928.

The Gold-Bug, by Edgar Allan Poe, foreword by Hervey Allen, notes on the text by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, Rimington & Hooper, 1928. Another edition: Garden City, Doubleday Doran & Co., Inc., 1929. [page 34:]

Doings of Gotham, by Edgar Allan Poe, as described in a series of letters to the editors of the Columbia Spy [[Columbia Spy]]; together with various editorial comments and criticisms by Poe; now first collected by Jacob E. Spannuth; with a preface, introduction, and comments by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. Pottsville, Pa. J. E. Spannuth, 1929.

A Child’s Reminiscence, by Walt Whitman; collected by Thomas O. Mabbott and Rollo G. Silver; with an introduction and notes. Seattle, University of Washington Book Store, 1930.

Brownie, by George Gissing; now first reprinted from the Chicago Tribune together with six other stories attributed to him, with introductions by George Everett Hastings, Vincent Starrett, Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, Columbia University Press, 1931.

A Catalogue of Illinois Newspapers in the New-York Historical Society, by Thomas O. Mabbott and Philip D. Jordan. Springfield, III. Journal Printing Company, 1931.

Works of John Milton, Columbia University Press, 1931-1938. Volume 1. The Greek and Latin Poems. Edited by W. P. Trent in collaboration with T. O. Mabbott.

Volume 12. An Early Prolusion by John Milton and miscellaneous correspondence in foreign tongues. Edited and translated by T. O. Mabbott and N. G. McCrea. English Correspondence by John Milton. Collected and edited by T. O. Mabbott. Correspondence of Milton and Mylius 1651-1652. Collected, edited, and translated by T. O. Mabbott and N. G. McCrea.

Volume 13. The State Papers of John Milton. Collected and edited by T. O. Mabbott and J. M. French.

Volume 18. The Uncollected Writings of John Milton. Edited by T. O. Mabbott and J. M. French.

Paste Prints and Sealprints. Metropolitan Studies, New York, 1932.

Al Aaraaf by Edgar Allan Poe. Reproduced from the edition of 1829. With a bibliographical note by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, Published for the Facsimile Text Society by Columbia University Press, 1933.

Volumes in the Einblattdrucke des fünfzehnten Jahrunderts, published by J. H. E. Heitz, Strasbourg. A series of separately printed 15th-century woodcuts. Each volume contains mounted facsimiles, mounted plates, and text by T. O. Mabbott. [page 35:]

Volume 78. Woodcuts and pasteprints of the Mabbott Collection, New York. 1933.

Volume 95. Relief prints in New York City, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Public Library, and the General Theological Seminary. 1938.

Volume 97. Relief prints in American public collections: Cambridge, Chicago, Evanston, Philadelphia, Providence, San Marino, and Washington. 1939.

Volume 99. Relief prints in American private and public collections in New York, Cambridge, Cincinnati, Kansas City. 1940.

The Complete Poetical Works of W. W. Lord, edited and with introduction by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, Random House, 1938.

Merlin, Baltimore, 1827; together with Recollections of Edgar A. Poe by Lambert A. Wilmer; edited with an introduction by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 1941.

Tamerlane and Other Poems, by Edgar Allan Poe. Reproduced in facsimile from the edition of 1827, with an introduction by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, published for the Facsimile Text Society by Columbia University Press, 1941.

The Raven and Other Poems, by Edgar Allan Poe. Reproduced in facsimile from the Lorimer Graham copy of the edition of 1845 with author’s corrections, with an introduction by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. New York, published for the Facsimile Text Society by Columbia University Press, 1942.

The Numismatic Review, New York. T. O. Mabbott editor, 1943-1948.

Selected Poetry and Prose of Edgar Allan Poe, with an introduction and notes by T. O. Mabbott. Random House (The Modern Library), 1951.

The Embargo, by William Cullen Bryant; facsimile reproductions of the editions of 1808 and 1809, with an introduction and notes by Thomas O. Mabbott. Gainesville, Fla., Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, 1955. [page 36:]

Prose Romances. The Murders in the Rue Morgue and The Man that Was Used Up. Photographic facsimile edition, prepared by George E. Hatvary and Thomas O. Mabbott, New York, St. John’s University Press, 1968.

Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe. Edited by Thomas Ollive Mabbott. Cambridge, Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press.

Volume I, Poems, 1969. This volume contains the “Annals,” a 43-page account of Poe’s life year by year.

Volumes II and III, Tales and Sketches, 1978, with the assistance of Eleanor D. Kewer and Maureen C. Mabbott.

————————————

The life of Edgar Allan Poe in A Readers’ Encyclopedia of American Literature, 1962, was written by T. O. Mabbott, as was the history of Numismatics in Collier’s Encyclopedia. His contributions to other works of reference and his innumerable articles have not been collected.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

Notes:

© 1980 and 2011, by The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, Inc.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

[S:1 - MPSEY, 1980] - Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Lectures - [Thomas Ollive] Mabbott as Poe Scholar: The Early Years (M. C. Mabbott, 1980)